I have to remember things. A patient once asked me how I recall so many specific details about his life, and I told him my office is like a planetarium. When the session begins, the details of my life fade, and I begin to see people and events in the patient’s life light up and connect. Because I don’t have the same blind spots as the patient, I can make different connections and name them without hesitation. When the patient walks out, the lights go back up and the sky fades to white. Then another patient enters, the light dims, another sky emerges, and before I know it, I’m immersed in a different world.

None of this happens by effort or intention; I just let it happen. I’m aware of how psychically charged these connections may be, but because I’m not invested in the sky looking one way or another, I’m free to simply report on what I’m seeing. On my own time, back among the stars and orbits of my own memory, I have my own pain points.

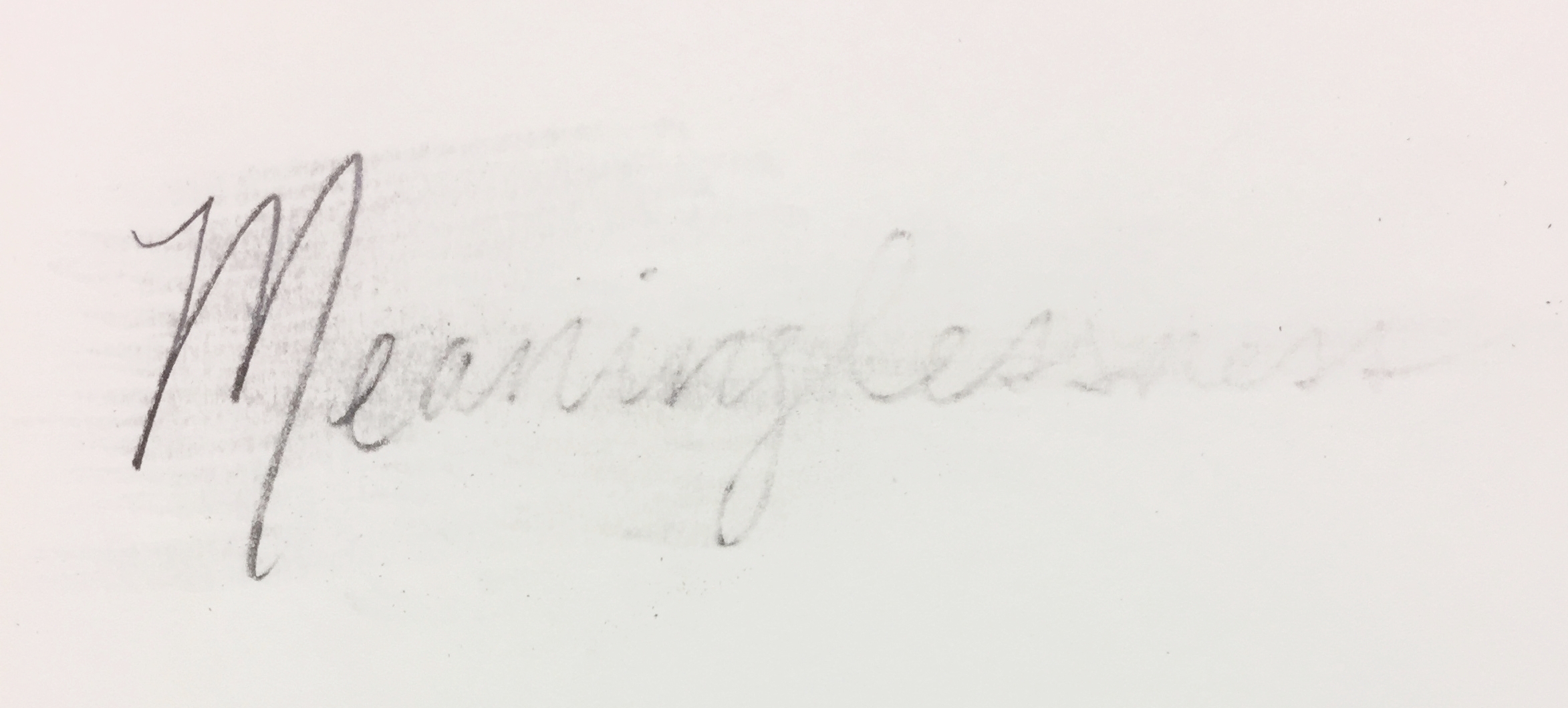

Memories make me wince, just like anyone else. No matter how analyzed a person is or how many sessions one has attended, memories can hurt. All the good songs are sad songs, the best memories are bittersweet, and no one is immune from the sting of nostalgia or the pain of regret. Happy moments smuggle an aftertaste of grief because they too are gone, along with everything else that has ever happened.

We like to think remembering makes us more human. But what if it’s forgetting that makes life bearable?

Between Remembering and Living

Revisiting our own lives also happens against our will. Remembering in the presence of a psychoanalyst can liberate us from painful repetition by exposing unconscious patterns to the interpretation of a less implicated observer. But in the privacy of our own minds, we feel deeply implicated in past events, and memory can feel like a trap. Living in the past becomes an obstacle to the elusive experience of now.

Like so many human paradoxes, we want two incompatible things at once: to live in the moment, and to remember. Philosopher John Gray puts it this way:

“It seems to be natural for human beings to want incompatible things—excitement and a quiet life, freedom and security, truth and a picture of the world that flatters their existence. A conflict-free existence is impossible for humans, and wherever it is attempted the result is intolerable to them.”1

We cannot go on without forgetting, yet we’re terrified of what it might mean to forget. The tortured amnesia of Alzheimer’s disease looks like a living death, but the gift of a functional memory compels us to spend much of our time reliving, rewriting, and regretting. Memory feels like identity, even as it slowly erodes our attention and our time.

Regret and the Unlived Life

One of Freud’s most enduring insights is that those who cannot remember are doomed to repeat. Freud understood his patients’ symptoms as the “return of the repressed”2: some aspect of a past experience or relationship that can’t be consciously recalled but finds expression in a bodily symptom, repetitive action, or perplexing emotion. Usually the repression was connected to a forbidden desire that was unwelcome to the patient’s sense of self and contemporary social norms.

These days, things are a bit different. Many of the forbidden desires that wracked Freud’s patients’ bodies are more socially acceptable, and perhaps to them it might seem that today we have nothing left to hide. Yet many of us are still left wanting, in part because we want contradictory things. We self-sabotage to service both sides of a desire, and through listening and interpretation, psychoanalysts help patients articulate these paradoxes. Once they can clearly see how and why they’ve gotten in their own way, they can finally move on.

To “move on” is really to forget, and paradoxically we must fully remember in order to forget. In Freud’s day, patients didn’t remember enough, and the job of the analyst was to interpret in order to help the patient remember. Nowadays, they tend to remember too much, and the analyst’s job is to help them consciously forget.

Both in repression and in more typical recall, it is important to find ways to clearly articulate memories as straightforwardly as possible. Optimally, this work of clarified remembering can then enable us to forget what we just fought to recall, but actively and consciously this time around. To be in the next moment, we must choose to forget, again and again.

The Ethics of Conscious Forgetting

People generally believe that remembering one’s history is an ethical necessity. When patients report to me how tortured they feel by painful memories, I think otherwise. For example, many patients are plagued by “the one who got away,” the person who slipped through their fingers. The memory prevents them from engaging in their lives and insidiously undermines the real relationships they are slowly sabotaging.

We underrate the ethics of forgetting: a deliberate, conscious refusal to let the past feed future suffering. We are not disinterested archivists within our own minds, and we do not remember dispassionately. We feel profoundly implicated in our secret autobiographies, and remembering often brings up self-criticism and deep regret. To dwell in these emotions is not to live at all.

Forgetting is not easy, in part because it requires us to give up a certain pleasure echoing in the blue notes of nostalgia and regret. The psychoanalytic term for this is jouissance, a dark enjoyment attached to emotionally intense experiences, including suffering. Regret often betrays a kind of passion, accompanied by racing thoughts, a pounding heart, and damp fingertips. In the revisionist history of regret, we imagine a smarter, bolder self saying the right thing to the right person at the right time. Fantasy influences memory, and an alternate world takes shape.

This airbrushed alternate history is what Adam Phillips calls “the unlived life”3, into which most of us invest far too much time and energy. It hinges on a notion that a life well lived would carry no regrets, and its reliving is loaded with jouissance. However, given the realities of the human condition, even if we had said and done the right things and thereby created a better life, unanticipated regrets would inevitably emerge. We rarely want just one thing, and correcting one regret merely moves the blue note to the next measure. One fewer regret does not end the cycle, yet we replay the past as a choose-your-own-adventure fantasy, torturing ourselves for not having lived fully redeemed lives. Jacques Lacan writes:

“The lack of forgetting is the same thing as the lack in being, since being is nothing other than forgetting.”4

Being requires forgetting. It enables forward movement and is a condition for the possibility of love, since to love someone requires forgetting. We cannot ignore the past’s impact, but we can refuse to let every conflict carry the echoes of every past disagreement. Living with others means responding to what is happening now, not replaying what has already happened. As the Zen proverb puts it, “Let go, or be dragged.”

The analyst remembers because someone has to. But patients can, if they allow themselves, begin to forget. This may be why patients often struggle to explain exactly what occurred in a transformative analytic treatment. The ancient Greeks knew that life is best lived, not rehashed. In the underworld, souls returning to life were required to drink from the river Lethe to forget their past, so they could begin again. If the psychoanalyst works in a planetarium, this river runs through it.

The Forgiveness in Forgetting

We make meaning through memory, but the world of memory is a kind of underworld that can make life deathly. Although capital-T Trauma attracts the most cultural attention, we mostly suffer from smaller memories: the mean thing you said, the fly ball you missed, the joke you shouldn’t have told, the friend you didn’t call, the one that got away. The wounds make us wince a little bit every day, and only by forgetting these things can we live again. We cannot deny an event, but we can refuse to suffer it endlessly.

To remember is to regret, and conscious forgetting gifts us the grace that makes living possible. Memories are not actually our lives; they are the psychological constellations surrounding us, not comprising life but illuminating it. A life is not only what has happened or what will happen next, but what it is right now.

Maybe the highest form of memory is remembering what and when to forget. Letting go enables us to forgive ourselves and those who have wronged us, and to live a little more. With a clear view of all the constellations of memory twinkling above, we can choose where to look. The “one” that got away was less a person and more a moment. We weren’t paying attention, and we missed it. There will be another, and forgetting gives us a chance to meet it.

John Gray, Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 17.

Sigmund Freud, “Further Remarks on the Neuro-Psychoses of Defence” (1896), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 3, pp. 157–185. The phrase “return of the repressed” also appears in later works such as Repression (SE XIV) and Moses and Monotheism (SE XXIII), and the concept runs throughout Freud’s work.

Adam Phillips, Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012).

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, trans. Russell Grigg (New York: W. W. Norton, 2007), p. 52.